Carter is the wizard behind Studio Shappy, where he’s working on different projects from design, illustration, woodworking, printmaking and more. We met up at his studio to talk about his Viscosity Monotypes series.

Tell me who you are and what you do?

My name is Carter Shappy. I am a visual artist, printmaker, designer, illustrator and art handler. My creative practice is a bit all over the place, for sustainability purposes, but I’m first and foremost a printmaker. My print work, similar to my practice as a whole, is pretty expansive—though I frequently explore intersections in art, science, psychedelia, perception, and other natural phenomena through the use of colorful, organic, sometimes “found” imagery. Mostly what I mean by “found,” is that it’s imagery, line or shape that’s been created collaboratively by means of some natural process. I’m very fond of letting nature do some of the conceptual and expressive leg work.

How did you get start with printmaking?

I think the first print I ever made was a reductive linoleum relief print. For those that don’t know what that is, it’s where one block of linoleum is carved into in multiple stages and printed with different colors at each stage. Each step more of the block is carved. What you have in the end, if done properly, is a beautiful multi-color print, with a nice variation of value and tone through overlapping and isolated color. I was in high school when I did that. It wasn’t until dabbling in community college art courses that I decided I should go to art school with a focus in printmaking. Both my high school and community college experiences helped solidify the beauty of print for me. I loved the process, the tools and the multiplicity of it. My family is composed of a long line of laborers, so I think the laborious, muscly parts of print spoke to me as well. I also come from very passionate home cooks. Print operates in a very similar headspace. Print has mise en place, just like a chef does. It requires tidiness and those with an eye for detail tend to thrive in it, just like in a good kitchen. I love the sort of specialized, laborious ebb and flow between the monotony of process and the attentive state of mind during problem solving. Print is magical. I guess, if you wanna get sappy about it, it’s alchemical. People love to say that.

Did you grow up in a creative family?

In certain ways, yes. My siblings are both creative people. They aren’t involved directly in the visual arts, but they have creative brains and ways of seeing the world. My father builds things and really most of my family is in someway building things. My mother was a huge nurturer of my creative growth. As I mentioned, I come from a long line of passionate home cooks, my mother being one of them. That is really where my families creativity shines. While there was some initial apprehension with certain members about my decision to attend a private art school for undergrad, everyone was mostly supportive. Today everyone is very intrigued and in general supportive of what I do and try to do, even if at times they don’t fully understand the concept. For people to be supportive of something that they may not fully understand, but to love and nurture that thing regardless…if that isn’t love than I’m a bit lost. I’m very fortunate in that regard.

What are project(s) working on right now?

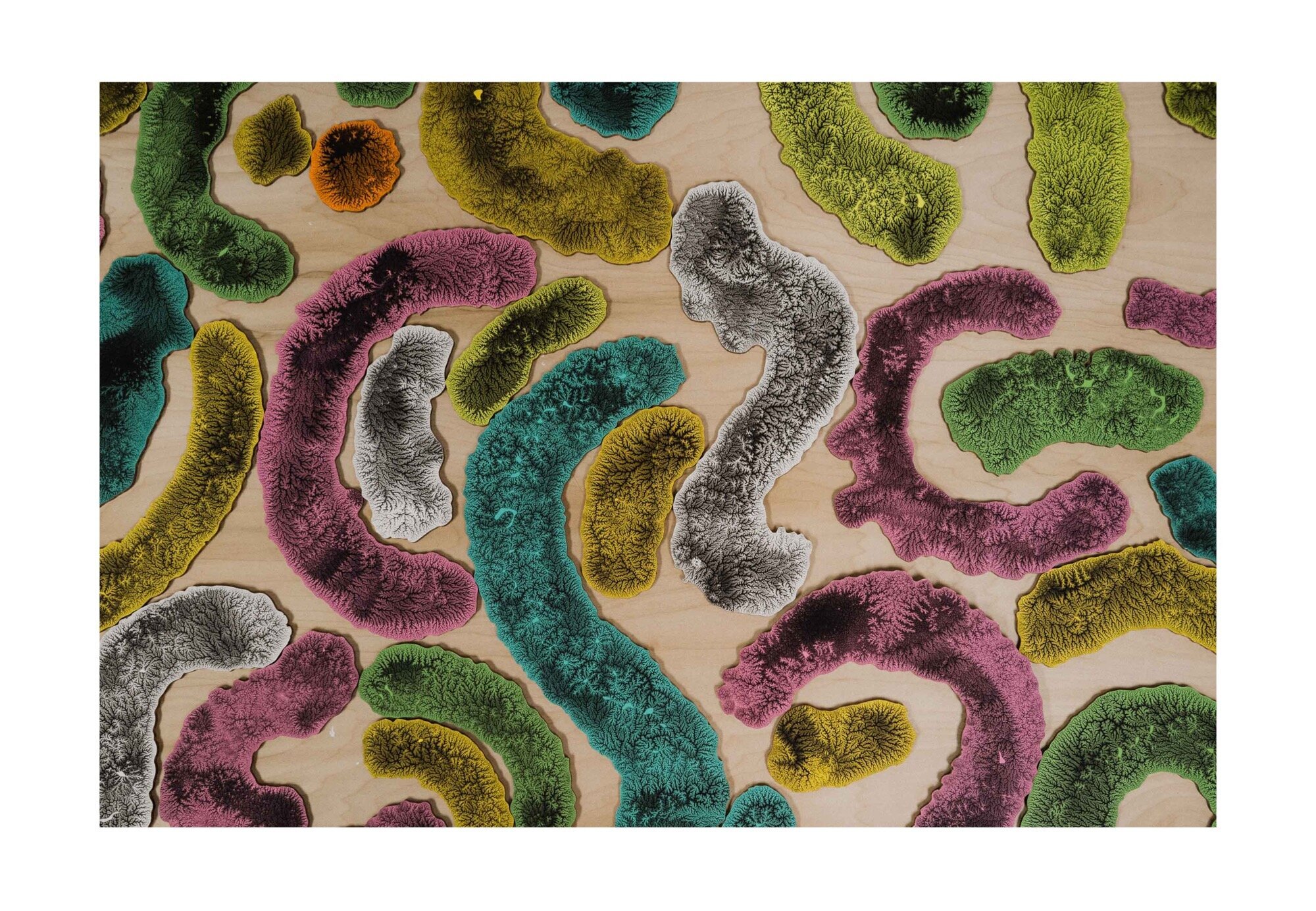

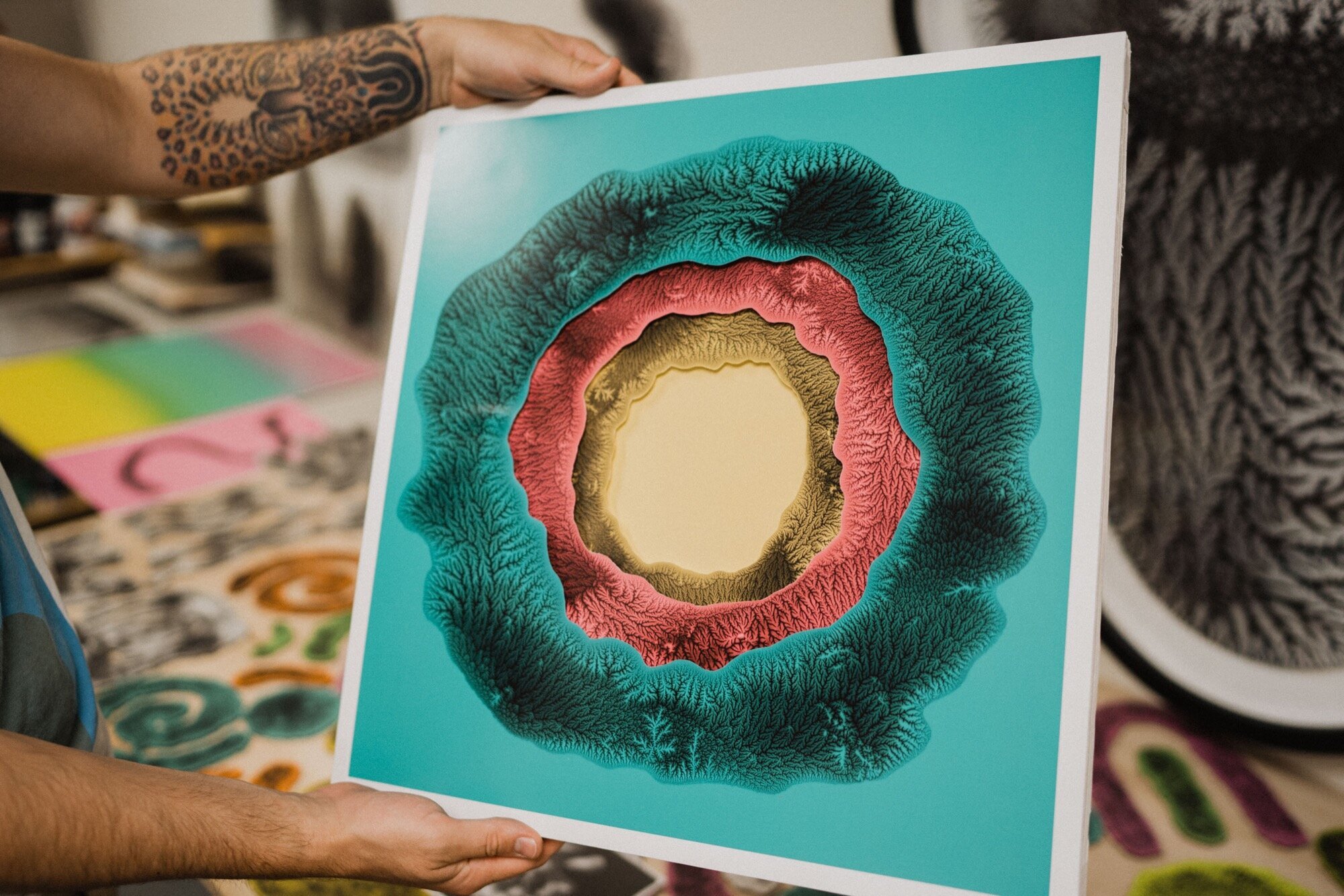

I’m currently working on a few projects, the most important to me being the production of new work in my viscosity monotype series. It’s a body of work that spans nearly 5 years now, most of which has been research and development. It all hinges on these highly intricate, complex branching patterns termed viscous fingering. Loosely speaking, these patterns are the result of a high viscosity liquid (in my gas actually a gas, i.e., air) being forced under intense pressure through a lower viscosity liquid (ink). It has a lot to do with the chemical and physical properties of ink, so in some ways it is a very quasi-scientific homage to the base ingredient of printmaking.

All of this new work stems from an accident at the printing press. I had turned over a copper plate that I was printing to clean the backside which was covered in ink. To my surprise it was embellished with these beautiful fractal growths. I decided to pull a print of it. That was 2015. I spent the following years trying to better understand how those patterns were formed and developing a set of conditions for them to be used expressively and in a semi-controlled manner. As I said, it is very much a collaborative process between myself and these natural phenomenon.

Why are you drawn to fractals and your Viscosity Monotypes project?

My fascination lies in the ubiquity of these patterns as represented, in plain sight, all throughout our world. They resemble river deltas, mountain ranges, plant growths, tree branches, cloud formations, crystalline structures, animal camouflage, human veins, and so much more. It’s a profound and seemingly obvious “discovery” to arrive at—that there is this kind of language or code that composes so much of what we see. I also think it permeates how we perceive the world around us and how we think. Maybe I’m obsessed and operating on some level of confirmation bias here, but it seems perception is not a linear, hierarchical construction, but in my opinion a complex self-generative lattice of thoughts…a kind fractal web of sorts.

Walk me through one of these pieces from start to finish.

The viscosity monotypes themselves (lots of other work sprouts from these prints) are made on a specially treated 1/8”inch hardboard. The surface has to be particularly non-porous for the patterns to generate properly. Sometimes a layer of color is painted on before they are treated. Sometimes they are left white. Then an appropriately viscous ink is laid down in lines of little dollops or beads, marking out a general shape that I’d like the patterns to proliferate within. The plate and ink is then covered with a plexiglass plate and introduced to extreme pressure using a special pressure point jig that I designed and several different types of traditional printing presses. Though I’ve dialed the process in, and have a general understanding of what will happen when I do X, Y, and Z, there is lots of failure. I look for clean boarders, a variety of grey values, clean gradations and depth of tone. The successful ones are continuous tone and photographic in nature. After printing, the shapes are then cut out along their borders with a scroll saw and finished with lacquer.

Do you think your work has changed since you started? If so, in what ways?

Certainly. Originally I was doing these prints on plastic and then scanning them in digitally and finding ways to use inkjet “reproductions”—which is where the idea for the cutouts came from. I was enlarging them and manipulating them digitally in other ways. I concluded that something was lost when they are enlarged too much. There is something about the scale of the original prints that is really appealing to me. It’s a dizzying level of complexity, and drops down to a scale that the eye can barely see at points. It forces me to get in close and visually burrow into those details. I love that process so I sought a way to use the prints themselves. That took time, as I like my art objects to be made with longevity in mind. I value craft and that which is archival. If I’m asking people to spend money on my work, that they spent many hours of their time to acquire, I want to be able to provide them with something that honors these traditional ideas of quality, i.e., longevity, meticulousness, specialization, and so on. It’s also an exciting problem to solve. How do I make this object, under a strict budget, as well as I can make it? Maybe it’s the old-fashioned laborer in me saying, “you have a job, do it well.”

Describe the space where you work.

My studio is located in Running With Scissors Art Studios in Portland, ME. It’s a multidisciplinary studio building and maker space with individual studios, a clay center, wood shop and print shop. I’ve been there for about 5 years. In conjunction with my private studio space I have developed and managed the print shop and wood shop as well.

Why do think you feel called to do something creative?

There must be some combination of genetic and circumstantial reasons for why certain people are creatively inclined. I’m not sure if I know why I have a proclivity for the arts, but I do know it’s in every ounce of blood I have. Making things and thinking deeply about myself and my surroundings are seemingly all I do. It makes up the bulk of my existence. It’s that old cliche response, “I don’t know why, I just have to.”

What inspires you?

I’m inspired by a vast assortment of things, but predominately my intrigue with sciences, natural phenomena, growth, and perception come to mind. I’m also heavily influenced by psychedelia, particularly the resurgence in clinical research on psychedelics. So much of what I feel like pointing to is this overwhelming experience that I feel when I look around my surroundings, not even necessarily when I’m in the forest or near the ocean. That experience is pure epiphany and personal discovery, like, “are you getting all of this? Look at the way this tornado of plastic whirls through that alley! Look at the surface of this water broken into a seemingly infinite number of smaller and smaller waves! Look at this amazing harmonious yet cacophonous sensory experience unfolding before our eyes!” I’m routinely blown away by, for lack of a more useful world, the beauty of the world around me. So there is this interest in seeing things like a child does, and in some ways like someone under the influence of psychedelics does. It’s such a simple, novel concept. It’s a phenomena that’s been with us forever. It’s wildly unoriginal, yet it is the most wonderful acknowledgment of the human experience—to be awestruck.

So I often gravitate towards things we loose track of, but that are so wonderfully magical that it seems hard one could ever forget about—such as this common fractal language that is everywhere. There are tons of artists operating in and around this space that influence my work as well. The artist influences go all over the place from 50s-60s modernists, to young emerging painters, illustrators and legendary comic book artists. It’s pretty eclectic.

What experience do you hope people have with your art?

I’ve spent a lot of time trying to unlearn this sort of didactic approach to talking about your work. Where you have an idea as an artist, and you scour in search of ways to justify your ideas and then feed it to your viewers. Art school teaches that. I loved my art school experience and learned so much from it, but I cannot deny that I learned more in spite of it. Some art forms belong in a didactic sphere, they thrive there and with good reason. There’s utility to it, but I prefer to let my work speak very plainly and visually for itself if I can. I do write a lot about the work, but I don’t want to over influence and otherwise steer someone away from their own personal discovery. I will say that I hope people, particularly with this newer work, feel intrigued enough to slow down and not zap through an in-person exhibition like they would on social media. I hope I’m making things that encourage investigation and people ask themselves that initial question of curiosity, “what am I looking at?” If I make it too obvious, or if I fill in all the blanks, I feel like an asshole.

What’s you favorite part of being a professional creative?

Undoubtedly the freedom to think, say, act and be what I like. It is the greatest privilege and honor in my life to do what I do. I have no idea how long it will last. It’s a precarious business endeavor, probably even perilous. I think it’s something we artists can take very easily for granted, this ability to think and speak freely. Most people don’t have this. The level of freedom that I have in my decision making, small and large, at any given day is profound. I hope it lasts a lifetime, but to be honest, I’m just grateful for what I’ve squeezed out of it already. I don’t mean to say there isn’t a cost to this freedom (ie., no guaranteed pay, lack of perceived public value, perpetual failure and rejection, and so on) but the pros very much outweighs the cons.

What’s the hardest part?

As with many things, the hardest part is a result of the best part. Dealing with all this freedom can be challenging. The possible avenues one could take ones work are infinite. How to funnel that creative freedom into something that is sustainable and achievable is incredibly difficult. Infinity paralysis is common, where I’m completely overwhelmed by all the possible places to take my practice and in turn am paralyzed in a state of anxiety, unable to assess which turn is the “right” one. It’s also difficult to be the sole scheduler, planner, coordinator, and goal setter. The level of self-discipline necessary to make this work, and to also make a living doing it, is still mind-blowing to me. Some people excel at it. I genuinely struggle with it.

What’s on your playlist right now?

A lot of soul/R&B/funk/hip hop. Durand Jones and the Indications, Amber Mark, Black Puma, Lady Wray, Charles Bradley, Vulfpeck, Thundercat, Frank ocean. On another genre, Andrew Birds instrumentals (all of his music too), Brian Eno’s new album with his brother Roger, Chassol, O Terno, Fleet Foxes, Iggy Pop’s Post Pop-Depression, and a just about everything else under the sun.

Where do you see your artwork going in the future?

I’m very project based. I latch on to ideas/processes and so on and let it fly. That being said I have a few thoughts in my notebook I’d love to entertain in the future. For some it may seem macabre, but I’m very fascinated in exploring the culture of death and dying, particularly here in the states. It’s something I think about a lot—both from a place of fear and fascination. I’d consider maybe leaning into that thought for future work, but I think I will always make work here and there that deals with older ideas. There’s always opportunity for development and refinement.

What advice would you give to someone wanting to start their own business in a creative field?

I hate that I’m about to provide you with the likes of a listicle, but here it is. It’s the easiest, quickest way to put forth some simple tips.

Take time to evaluate your strengths and weaknesses. Make a habit, even a schedule of refining your weaknesses. If you cannot change, seek an external assist. This is especially important for the business side of things. If you suck at managing your time, get an app that does it for you. If you have the money, hire someone to fill the voids—it’s a worthy investment. Most of us don’t thrive in a vacuum in and of ourselves. We all need help. Ask for it when you need it.

Find people whose work you admire or respect and befriend them. Buy them coffee and ask them how they do what they do.

Be sure there are people in your social circles who inspire you, build you up and support you.

Remain critical of yourself first and foremost, then of others when necessary. On a similar note, envy is rampant and self destructive. Don’t engage it.

Exercise your creative muscles in every aspect of your life. They can atrophy.

Know your industry and demand fair and reasonable payment. Exposure is almost entirely a bullshit concept, presented by unknowing or, worse, conniving opportunists.

Immerse yourself in your practice as much as you can.